The FODMAP concept was first published in 2005 as part of a hypothesis paper. In this paper, it was proposed that a collective reduction in the dietary intake of all indigestible or slowly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates would minimize stretching of the intestinal wall. This was proposed to reduce stimulation of the gut’s nervous system and provide the best chance of reducing symptom generation in people with IBS. At the time, there was no collective term for indigestible or slowly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates, so the term ‘FODMAP’ was created to improve understanding and facilitate communication of the concept.

The low FODMAP diet was originally developed by a research team at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. The Monash team undertook the first research to investigate whether a low FODMAP diet improved symptom control in patients with IBS and established the mechanism by which the diet exerted its effect. Monash University also established a rigorous food analysis program to measure the FODMAP content of a wide selection of Australian and international foods.

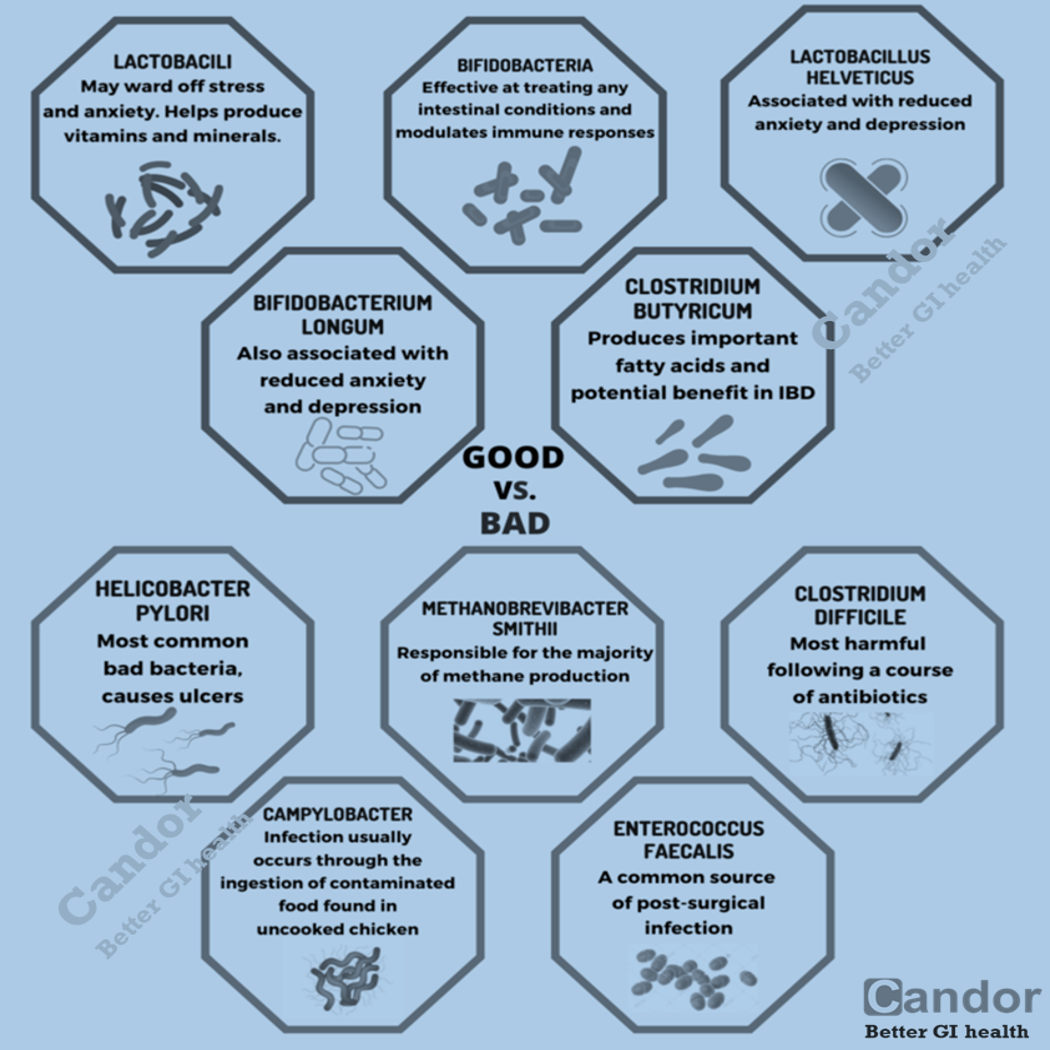

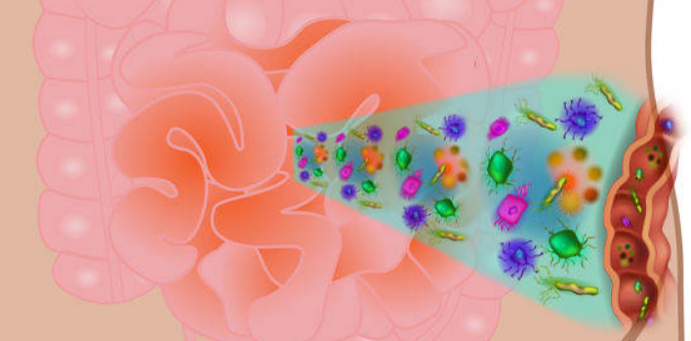

Food substances that can induce distension are those that are poorly absorbed in the proximal small intestine, osmotically active, and fermented by intestinal bacteria with hydrogen (as opposed to methane) production. The small molecule FODMAPs exhibit these characteristics.

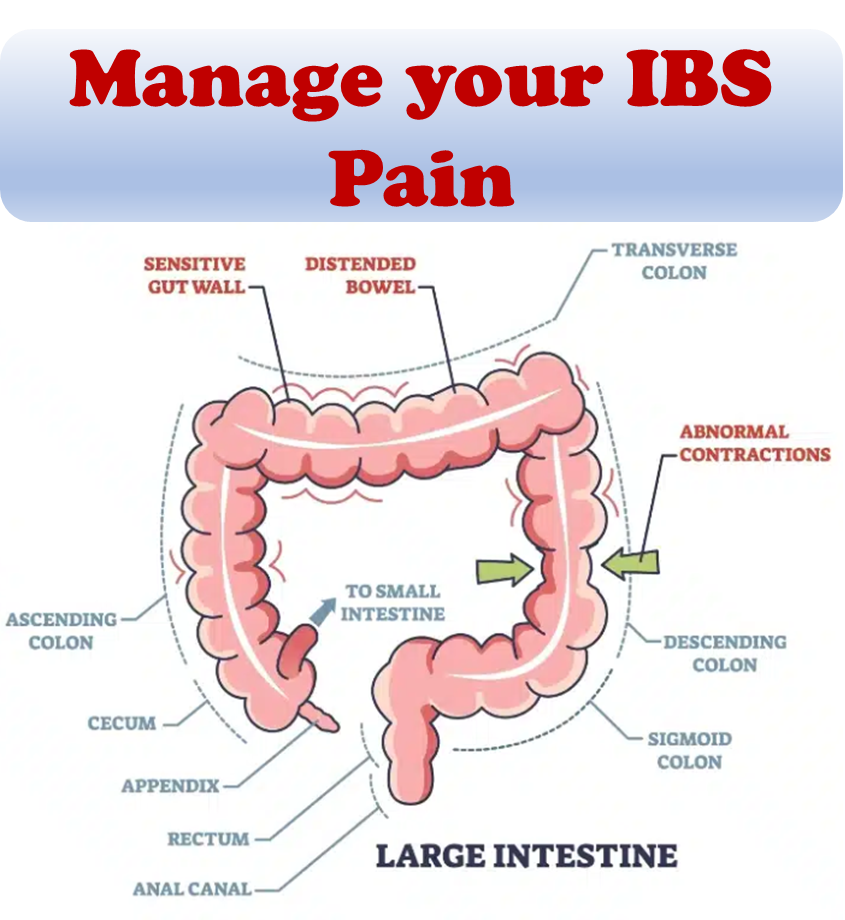

Over many years, there have been multiple observations that ingestion of certain short-chain carbohydrates, including lactose, fructose and sorbitol, fructans and galactooligosaccharides, can induce gastrointestinal discomfort similar to that of people with irritable bowel syndrome.

These studies also showed that dietary restriction of short-chain carbohydrates was associated with symptoms improvement. These short-chain carbohydrates (lactose, fructose and sorbitol, fructans and GOS) behave similarly in the intestine. Firstly, being small molecules and either poorly absorbed or not absorbed at all, they drag water into the intestine via osmosis. Secondly, these molecules are readily fermented by colonic bacteria, so upon malabsorption in the small intestine they enter the large intestine where they generate gases (hydrogen, carbon dioxide and methane).

The dual actions of these carbohydrates cause an expansion in volume of intestinal contents, which stretches the intestinal wall and stimulates nerves in the gut. It is this ‘stretching’ that triggers the sensations of pain and discomfort that are commonly experienced by IBS sufferers.

So, what are FODMAPs?

FODMAPs refer to a specific group of carbohydrates known as fermentable short-chain carbohydrates. These types of carbs can be challenging for some individuals to digest effectively. The acronym FODMAP stands for Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols. To alleviate discomfort and provide relief for your digestive system, the low FODMAP diet involves a temporary restriction of these carbohydrates. By eliminating these potential irritants, you allow your gut lining an opportunity to heal and restore a healthier balance of gut bacteria. As you experience improvements in your symptoms, the low FODMAP diet can help you identify which foods to limit in the future for better management of your digestive health.

What exactly are FODMAPs? FODMAPs can be described as follows:

- Fermentable: These are types of food that serve as a source of nourishment for the bacteria residing in your gut, leading to a process called fermentation where gases are produced.

- Oligosaccharides: These are soluble plant fibers known as prebiotics, which act as food for the beneficial bacteria in your gut. Examples of oligosaccharides include onions, garlic, beans/lentils, and certain wheat products. Sensitivity to oligosaccharides may explain cases of non-celiac gluten sensitivity. It’s worth noting that gluten-free grains contain fewer fermentable sugars compared to grains containing gluten, which means some individuals who believe they are gluten-sensitive might actually be sensitive to the oligosaccharides present in wheat products.

- Disaccharides: This group comprises lactose, the fermentable sugar found in dairy and human milk. Lactose intolerance is one of the most common food intolerances globally.

- Monosaccharides: Fructose, the sugar present in fruit, falls into this category as the fermentable sugar. However, not all fruits are affected by fructose in the same quantities or proportions.

- Polyols: These are sugar alcohols commonly used as artificial sweeteners and can also be found naturally in certain fruits.

Why are FODMAPs challenging to digest? FODMAPs are considered fermentable short-chain carbohydrates. In simpler terms, they are chains of sugar molecules that can be broken down and fermented by the bacteria in your gut. Normally, sugar molecules need to be broken down into individual units to be absorbed through the small intestine. However, FODMAPs cannot be broken down, leading to their inability to be absorbed in that region. Consequently, the small intestine absorbs extra water to aid in moving the FODMAPs to the large intestine. Once there, the bacteria in the colon have a feast fermenting these undigested carbohydrates, resulting in the production of gases and fatty acids within your gut.

Who can benefit from incorporating a low FODMAP diet?

The low FODMAP diet is commonly recommended for individuals diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO). Extensive studies have shown that a significant number of people with these conditions experience notable improvements through this dietary approach. Additionally, it can serve as a short-term elimination diet for anyone seeking to identify specific food triggers causing digestive issues. By eliminating common problem foods and reintroducing them systematically, you can observe how your system reacts. The low FODMAP diet is just one of several elimination diets available to uncover potential food sensitivities.

What does the low FODMAP diet entail?

The diet encompasses three main phases: an elimination phase, a reintroduction phase, and a personalized maintenance phase. During the elimination phase, you will avoid consuming high-FODMAP foods, including specific fruits, vegetables, dairy products, and grains. Although the initial impression may make the elimination phase seem restrictive, there is still a substantial variety of foods within each category that you can enjoy. Following this phase for two to four weeks, you will proceed to the reintroduction phase, where you systematically reintroduce foods back into your diet. The maintenance phase is tailored to your specific needs, incorporating what works well for you and omitting what triggers symptoms.

What foods are allowed on the low FODMAP diet?

Various fruits, vegetables, grains, and proteins have different levels of FODMAPs. Some foods are acceptable in limited quantities but may cause discomfort when consumed in larger amounts. For instance, most legumes and processed meats are high in FODMAPs, while plain-cooked meats, tofu, and eggs serve as low FODMAP protein sources. Certain fruits like apples, watermelon, and stone fruits are high in FODMAPs, whereas grapes, strawberries, and pineapples are considered acceptable. A ripe banana, although high in fructose, can be enjoyed in smaller portions, such as a third cut up in your cereal, or a whole one if it’s slightly underripe. A registered dietitian can provide specific guidelines tailored to your dietary needs.

Which high FODMAP foods should be avoided?

Determining which high-FODMAP foods to avoid is a personal journey within the low FODMAP diet. The answer will vary for each individual. The objective of the diet is not to permanently eliminate “bad” foods but rather to investigate if FODMAPs contribute to your symptoms and, if so, which ones. It’s important to note that some individuals may not experience any improvement during the elimination phase, in which case there may be no need to proceed to the next phase. However, for those who do notice positive changes, it becomes crucial to reintroduce foods systematically to differentiate between trigger foods and those that can be tolerated. Ultimately, many individuals discover that only one or two FODMAP food groups bother them. The ultimate goal of the low FODMAP diet is to expand your dietary options as much as possible.

What steps should I take before beginning the low FODMAP diet?

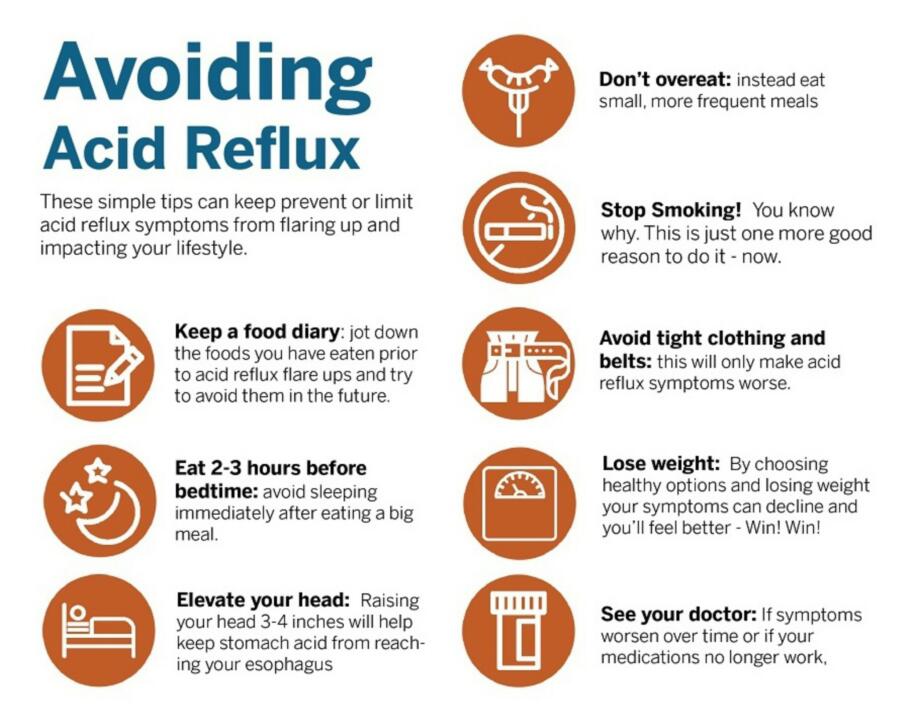

- Seek guidance from a healthcare professional: It’s essential to consult a reliable healthcare provider, such as a registered dietitian or a gastrointestinal (GI) specialist, before starting the low FODMAP diet. Whether you have a diagnosed GI disease or are exploring potential causes for your symptoms, these experts can offer valuable insights and alternative ideas to consider before implementing the diet. They can guide you through the nuances of the diet, provide helpful shopping and menu guides, and assist you with troubleshooting any questions or challenges that may arise. Having a knowledgeable guide by your side can significantly improve your success in following the diet effectively.

- Plan and prepare in advance: The low-FODMAP diet requires a significant investment of time and effort, albeit temporarily. Before you begin, allocate a dedicated period that won’t clash with important events or obligations. It’s crucial to commit to the process wholeheartedly, as cheating or deviating from the diet can compromise the entire experiment. Clear your fridge and pantry of high-FODMAP foods, and take the time to plan out your menus in advance. Make sure you have ingredients for a few simple go-to meals that you can prepare easily and enjoy without complications.

How long should I adhere to the low FODMAP diet?

Phase 1: The elimination phase typically lasts between two to six weeks, as recommended by healthcare providers. This phase requires patience, as it takes time for the diet to take effect and for your symptoms to alleviate. If you have small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), you might experience detox symptoms that initially worsen before improving, as the process involves starving overgrown gut bacteria. However, even if you feel great during the elimination phase, remember that it is not intended to be a permanent solution. It’s crucial to determine which foods you can reintroduce and tolerate, as a more balanced and varied diet is easier to maintain in the long run while ensuring adequate intake of essential micronutrients.

Phases 2 & 3: The reintroduction phase varies in duration but typically lasts around eight weeks. During this phase, you remain on the low-FODMAP diet while gradually reintroducing one high-FODMAP food from each category, one at a time. You carefully test each food by gradually increasing the quantity to determine your tolerance threshold. Between each test, you return to the strict elimination diet for a few days to avoid any crossover effects. Once you identify which foods work well for you and which ones trigger symptoms, you and your healthcare provider can develop a sustainable and nutritious long-term diet plan tailored to your specific needs.

What if the low FODMAP diet doesn’t provide the desired results?

The low-FODMAP diet is an experiment, and it may not yield the desired outcomes for everyone. However, if you follow the diet under expert guidance, it is considered safe to try. Your healthcare provider will monitor your overall nutrition and address any deficiencies or weight loss that may occur. They will also guide you on when it’s appropriate to discontinue the diet and explore alternative options. While the low-FODMAP diet has a high success rate for individuals with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), approximately 25% may not experience significant benefits. For other conditions such as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and functional dyspepsia, research is more limited but suggests potential symptom management benefits. If the low-FODMAP diet doesn’t provide the desired results, don’t lose hope. There are other types of elimination diets, tests, and therapies available to explore on your journey toward improved digestive health.

Key takeaways and considerations

A low FODMAP diet consists of the global restriction of all fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs), that is recommended only for a short time. A low FODMAP diet is recommended for managing patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and can reduce digestive symptoms of IBS including bloating and flatulence.

- A low FODMAP diet might help to improve short-term digestive symptoms in adults with irritable bowel syndrome, but its long-term use can have negative effects because it causes a detrimental impact on the gut microbiota and metabolome.

- It should only be used for short periods of time and under the advice of a specialist.

- The use of a low FODMAP diet without medical advice can lead to serious health risks, including nutritional deficiencies and misdiagnosis, so it is advisable to conduct a complete medical evaluation before starting a low FODMAP diet to ensure a correct diagnosis and that the appropriate therapy may be undertaken.

- Since the consumption of gluten is suppressed or reduced with a low FODMAP diet, the improvement of the digestive symptoms with this diet may not be related to the withdrawal of the FODMAPs, but of gluten, indicating the presence of an unrecognized celiac disease, avoiding its diagnosis and correct treatment.

- A low FODMAP diet is highly restrictive in various groups of nutrients, can be impractical to follow in the long-term and may add an unnecessary financial burden.

References:

- Gibson PR, Shepherd SJ (February 2010). “Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: The FODMAP approach”. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

- Barrett JS (March 2017). “How to institute the low-FODMAP diet”. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology (Review).

- Gibson PR (March 2017). “History of the low FODMAP diet”. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology (Review).

- Biesiekierski JR, Rosella O, Rose R, Liels K, Barrett JS, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG (April 2011). “Quantification of fructans, galacto-oligosacharides and other short-chain carbohydrates in processed grains and cereals”. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics.