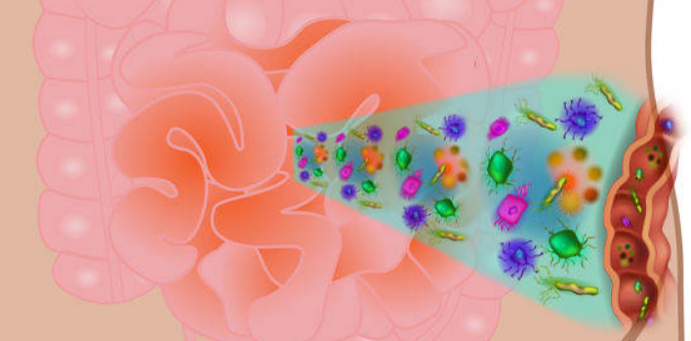

Small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), also termed bacterial overgrowths, or small bowel bacterial overgrowth syndrome (SBBOS), is a disorder of excessive bacterial growth in the small intestine. Unlike the colon (or large bowel), which is rich with bacteria, the small bowel usually has fewer than 10,000 organisms per ml. A common misconception is that SIBO diagnosis affects only a limited number of people, such as those with an anatomic abnormality of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract or those with a motility disorder. However, SIBO may be more prevalent than previously thought. Small bowel bacterial overgrowth syndrome is treated with an elemental diet or antibiotics, which may be given in cycles to prevent development of tolerance.

SIBO diagnosis

The diagnosis of bacterial overgrowth can be made by physicians in various ways. Malabsorption can be detected by the D-xylose test. D-xylose is a monosaccharide, or simple sugar, that does not require enzymes for digestion prior to absorption. Its absorption requires an intact mucosa only. The D-xylose test involves having a patient drink a certain quantity of D-xylose, and measuring levels in the urine and blood. Little or no D-xylose in the urine and blood indicates issues with absorption in the small intestine.

Another common way to diagnose SIBO is by undergoing a Hydrogen breath test. This is a test for bacterial overgrowth using glucose. Glucose is a sugar that will be broken down by bacteria (if present) in the small bowel. The breakdown of glucose releases hydrogen or methane gas. The breath sample will be analyzed for hydrogen or methane content to determine if you are able to properly break down the glucose or if you have bacterial overgrowth. If you are not able to break down the glucose, then your breath test is positive and you have SIBO.

Small intestine aspirate and fluid culture is currently the gold standard test for bacterial overgrowth. To obtain the fluid sample, doctors pass a long, flexible tube (endoscope) down the patient’s throat and through the upper digestive tract to the small intestine. A sample of intestinal fluid is withdrawn and then tested in a laboratory for the growth of bacteria.

What are the symptoms of SIBO?

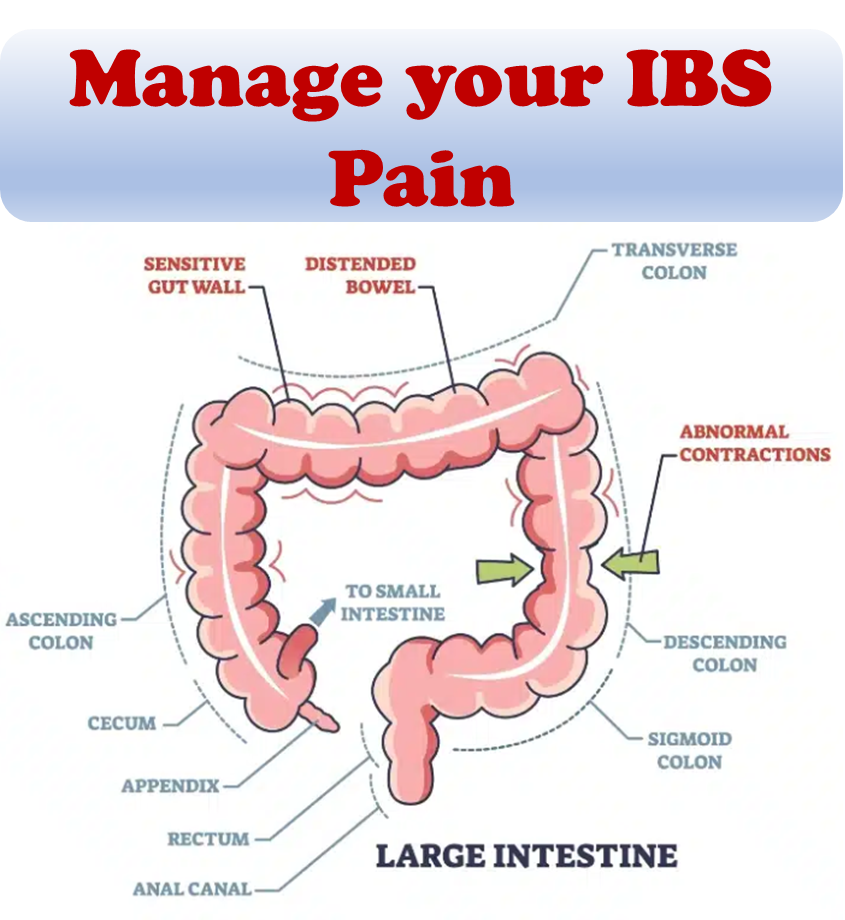

The symptoms of SIBO can mimic those of various other gastrointestinal disorders, and often, another underlying condition may have played a role in causing SIBO. Depending on the severity of your condition, you may experience a range of these symptoms:

Chronic diarrhea, bloating, abdominal swelling, gas and belching, abdominal pain or fullness after eating, alteration of bowel habits (constipation, diarrhea or alternating with both).

What are the consequences of untreated SIBO?

While the discomfort of common SIBO symptoms like gas, bloating, abdominal pain, and distension can be challenging, leaving SIBO untreated can lead to more severe complications with lasting effects. Malabsorption of fats, proteins, and carbohydrates can result in malnutrition and deficiencies in vital vitamins. Specifically, a deficiency in vitamin B12 can lead to neurological issues and anemia, while poor calcium absorption may contribute to long-term osteoporosis or kidney stone formation.

What leads to SIBO?

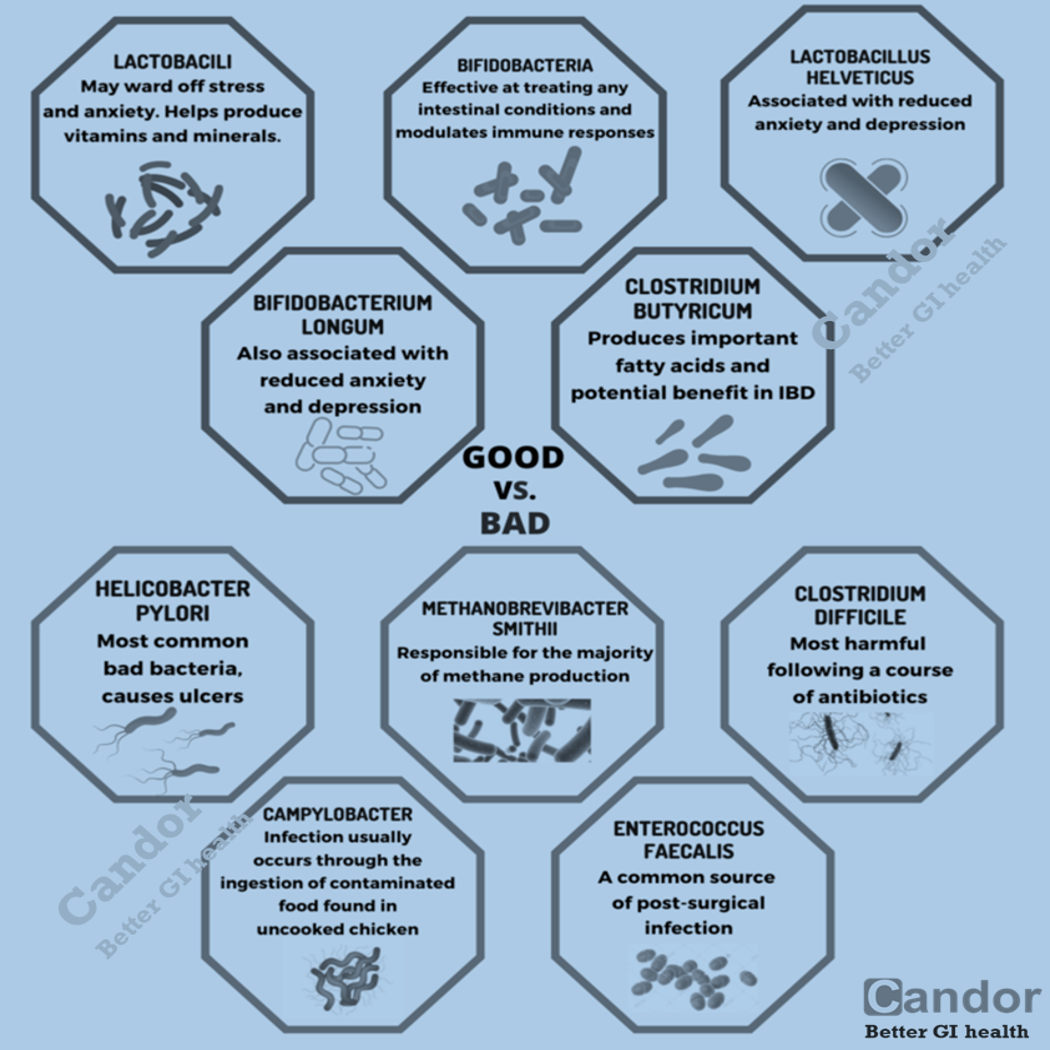

Reduced stomach acid (hypochlorhydria) diminishes the body’s ability to regulate bacterial growth. Factors contributing to lower stomach acid levels include:

- Infection with H. Pylori.

- Prolonged usage of medications like antacids and proton pump inhibitors.

- Gastric bypass surgery.

Dysmotility in the small intestine refers to delayed waste elimination, allowing bacteria to proliferate. Some dysmotility disorders are:

- Gastroparesis.

- Intestinal pseudo-obstruction.

- Hypothyroidism.

Structural issues in the small intestine hinder motility and clearance of bacteria, creating spaces for accumulation. These issues may arise from gastrointestinal diseases or surgical complications, such as small bowel diverticulosis, small bowel obstructions and abdominal adhesions. Overuse of certain medications can disrupt the normal flora balance, including antibiotics, narcotics and gastric acid suppressants.

What are the risk factors for SIBO?

Advanced age correlates with lower stomach acid and motility, along with increased medication use that may promote SIBO. Medical interventions like abdominal surgery and radiation can cause structural and mucosal damage in the small intestine, affecting immunity. Immunodeficiency disorders impact intestinal immunity to specific bacteria.

Various gastrointestinal conditions affect motility or cause structural problems, such as:

- Diabetes.

- Lupus.

- Celiac disease.

- Inflammatory bowel diseases.

- Irritable bowel syndrome.

- Pancreatitis.

- Colon cancer.

- Scleroderma.

- Chronic renal failure.

- Cirrhosis of the liver.

What foods can trigger SIBO?

Although food isn’t the primary cause of SIBO, certain foods can promote overgrowth in the small intestine. Avoiding these favored foods can help reduce overgrowth and SIBO symptoms. Commonly restricted items in SIBO diets include:

- Sugars and sweeteners.

- Fruits and starchy vegetables.

- Dairy products.

- Grains.

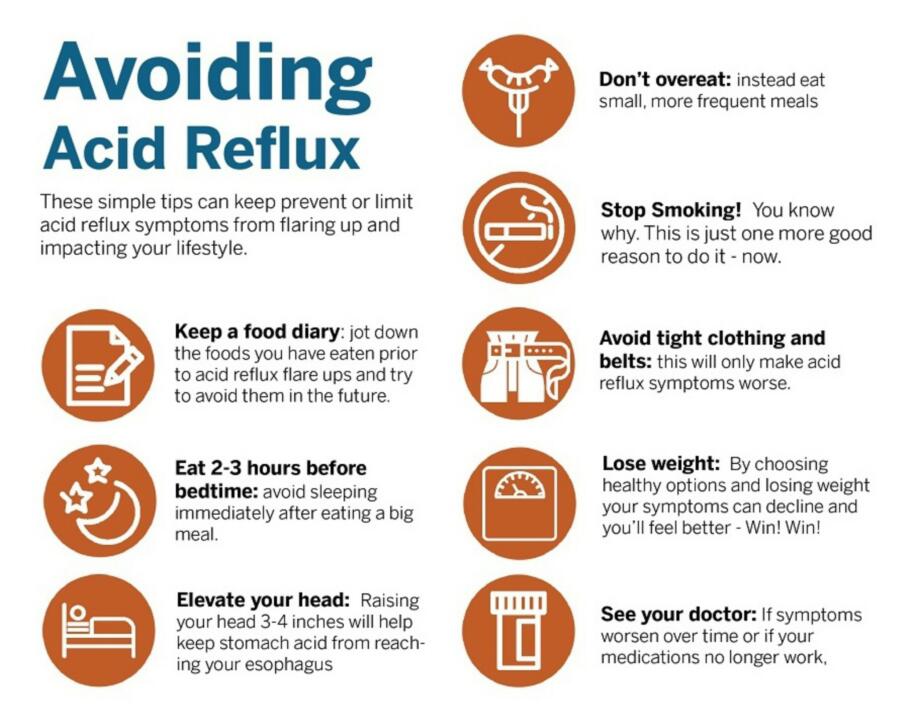

SIBO often arises as a complication of another underlying condition and can cause its own set of complications. Effective treatment of SIBO involves addressing several aspects:

- Managing the bacterial overgrowth itself.

- Addressing any complications that have arisen due to SIBO.

- Identifying and treating the root cause of SIBO.

How is SIBO treated?

Typically, antibiotics are prescribed as the primary medical treatment for bacterial overgrowth. Healthcare providers then focus on managing acute complications, which may involve nutritional support and supplementation to address vitamin and mineral deficiencies. They may also recommend a short-term strict diet to alleviate symptoms, followed by a modified long-term diet plan to restore proper nutrition and prevent bacterial overgrowth recurrence.

Ultimately, healthcare providers aim to pinpoint and treat the underlying cause of SIBO, which may necessitate further diagnostic tests. For individuals with motility disorders, motility agents may be prescribed to stimulate intestinal movement. In cases where structural issues are identified, surgery may be recommended to correct them.

Bacterial overgrowth is usually treated with a course of antibiotics although some experts recommend probiotics as first line therapy with antibiotics being reserved as a second line treatment for more severe cases. A course of one week of antibiotics is usually sufficient to treat the condition. However, if the condition recurs, antibiotics can be given in a cyclical fashion in order to prevent tolerance. For example, antibiotics may be given for a week, followed by three weeks off antibiotics, followed by another week of treatment. Alternatively, the choice of antibiotic used can be cycled.

References:

- Bures J, Cyrany J, Kohoutova D, et al. (2010) “Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome”. World J Gastroenterol.

- Dukowicz AC, Lacy BE, Levine GM. (2007) “Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: a comprehensive review”. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY).

- Roland BC, Ciarleglio MM, Clarke JO, et al. (2015) “Small Intestinal Transit Time Is Delayed in Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth”. J Clin Gastroenterol.