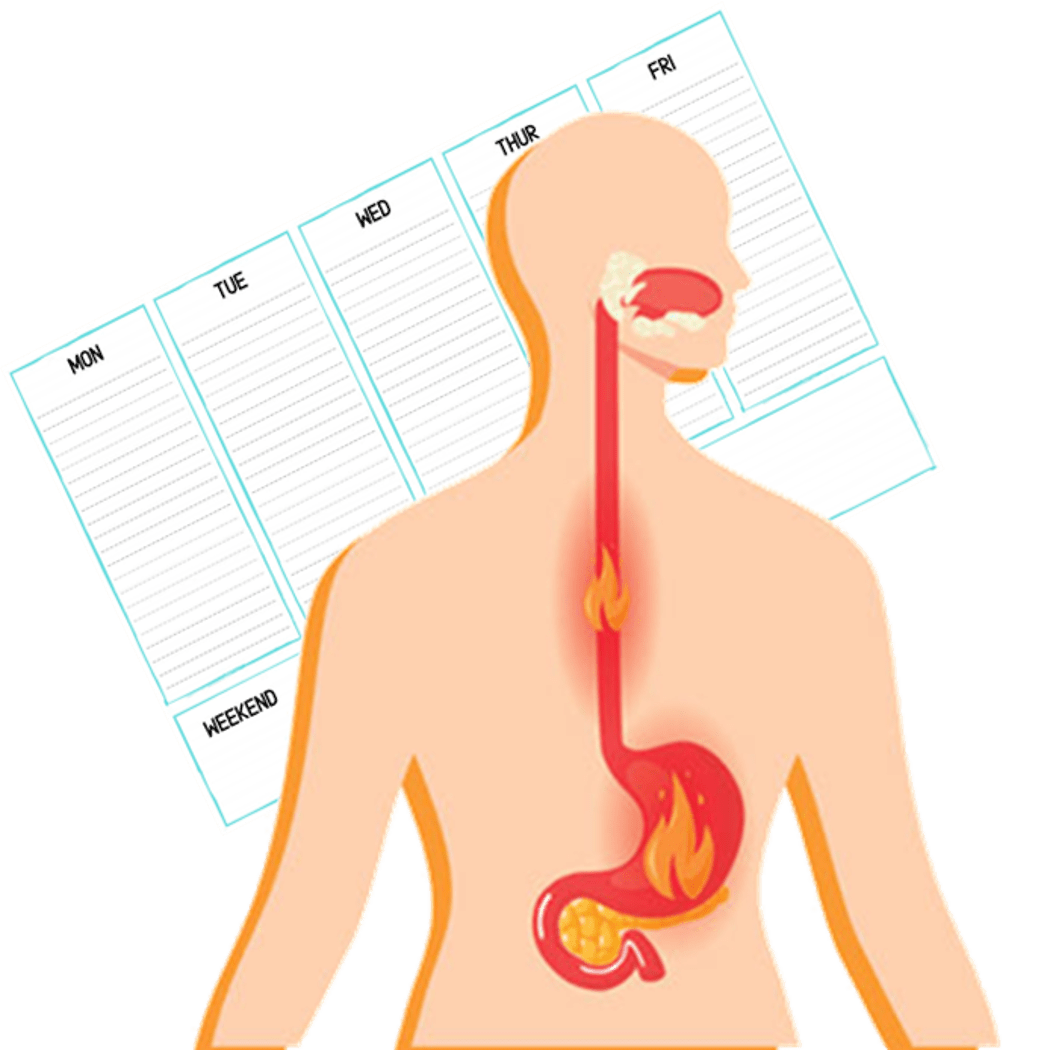

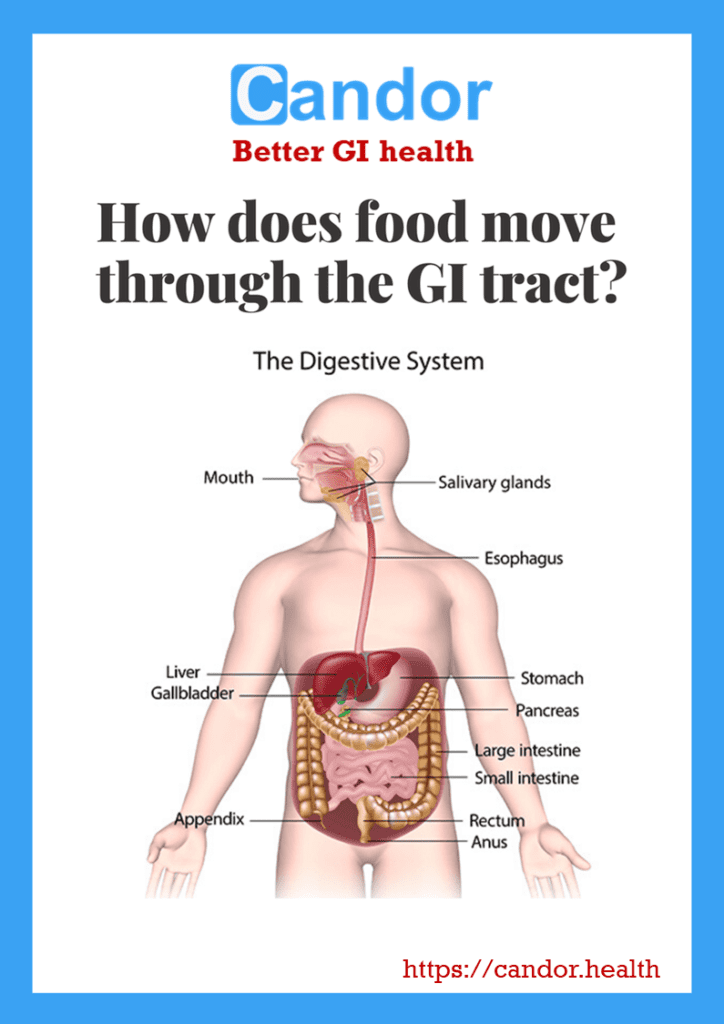

The gastrointestinal tract, also known as the digestive tract or alimentary canal, is a long, continuous tube that extends from the mouth to the anus. It plays a crucial role in the digestion, absorption, and elimination of food and waste products from the body. The major organs and structures that make up the gastrointestinal tract include:

- Mouth: The digestive process begins in the mouth, where food is chewed and mixed with saliva, which contains enzymes that help break down carbohydrates.

- Esophagus: This muscular tube connects the mouth to the stomach and transports swallowed food from the mouth to the stomach through a series of coordinated muscle contractions called peristalsis.

- Stomach: The stomach is a muscular organ that receives food from the esophagus. It secretes gastric juices, including acid and enzymes, that further break down food and initiate the digestion of proteins. The stomach also helps regulate the release of food into the small intestine.

- Small Intestine: The small intestine is the longest part of the gastrointestinal tract and is divided into three sections: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. It is the primary site for the digestion and absorption of nutrients. Enzymes from the pancreas and bile from the liver help break down fats, proteins, and carbohydrates into their basic building blocks, which are then absorbed through the lining of the small intestine into the bloodstream.

- Liver: While not a part of the digestive tract itself, the liver plays a vital role in digestion. It produces bile, a substance that helps emulsify fats and aids in their digestion and absorption. Bile is stored in the gallbladder and released into the small intestine when needed.

- Pancreas: The pancreas is another accessory organ that assists in digestion. It produces digestive enzymes that are released into the small intestine to further break down carbohydrates, proteins, and fats.

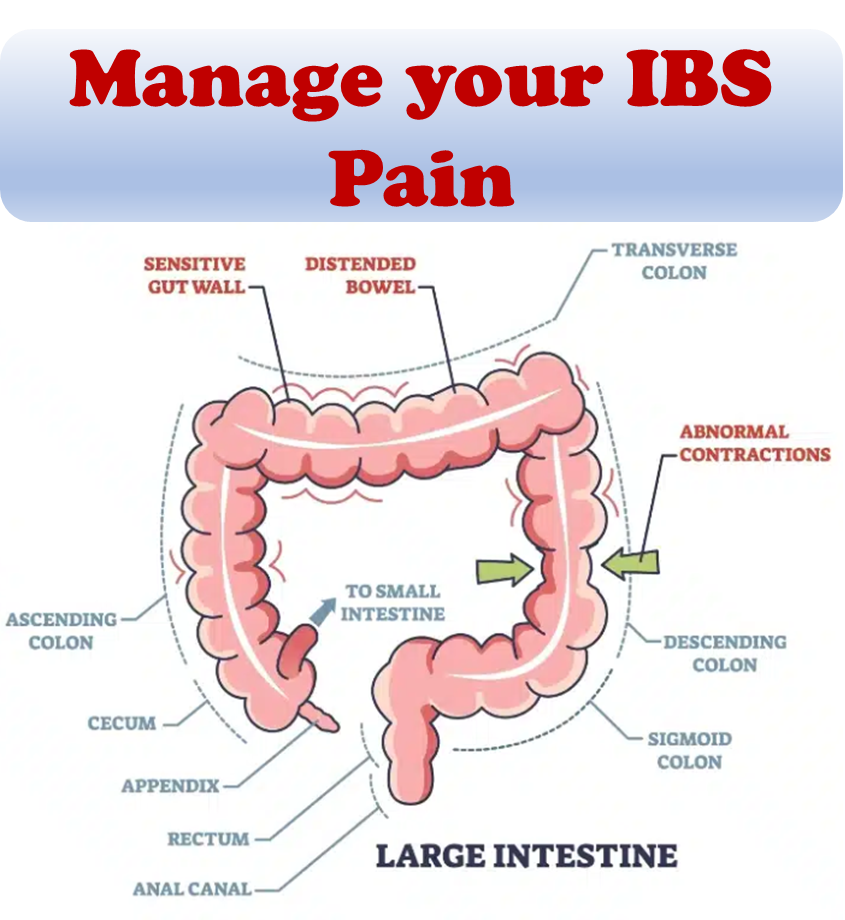

- Large intestine (Colon): The large intestine receives undigested food particles, water, and electrolytes from the small intestine. Its primary function is to absorb water and electrolytes, form and store feces, and facilitate the elimination of waste products from the body.

- Rectum and anus: The rectum is the lower part of the large intestine that stores feces until they are expelled from the body through the anus during defecation.

The gastrointestinal tract works in coordination with various organs and structures to ensure the proper digestion and absorption of nutrients while eliminating waste materials.

The process of peristalsis is responsible for the movement of food throughout the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Within the GI tract, the large hollow organs possess a layer of muscular tissue that facilitates their motion.

This motion propels food and liquids through the GI tract, promoting the mixing of contents within each organ. The muscles behind the food contract and exert pressure to propel it forward, while the muscles ahead of the food relax to enable its movement.

Let’s explore the journey of food through the GI tract:

- Mouth: The journey commences when food is consumed. The tongue pushes the food into the throat, and a small tissue flap known as the epiglottis folds over the windpipe, preventing choking. Subsequently, the food enters the esophagus.

- Esophagus: After swallowing, the process becomes automatic. The brain signals the muscles in the esophagus, initiating peristalsis.

- Lower esophageal sphincter: As food reaches the end of the esophagus, a circular muscle called the lower esophageal sphincter relaxes, allowing food to pass into the stomach. Normally, this sphincter remains closed to prevent the backward flow of stomach contents into the esophagus.

- Stomach: Once food enters the stomach, its muscular walls mix the food and liquids with digestive juices. Gradually, the stomach empties its contents, referred to as chyme, into the small intestine.

- Small intestine: The muscles of the small intestine blend the food with digestive juices from the pancreas, liver, and intestine. They propel this mixture forward to facilitate further digestion. The walls of the small intestine absorb water and the digested nutrients, delivering them to the bloodstream. Simultaneously, peristalsis continues, moving waste products of digestion into the large intestine.

- Large intestine: Waste products in the form of undigested food particles, fluids, and older cells from the GI tract lining are processed in the large intestine. Here, water is absorbed, transforming the waste into stool. Peristalsis assists in propelling the stool toward the rectum.

- Rectum: The rectum, located at the lower end of the large intestine, serves as a storage site for stool until it is expelled through the anus during a bowel movement.

References:

- G., Hounnou; C., Destrieux; J., Desmé; P., Bertrand; S., Velut (2002-12-01). “Anatomical study of the length of the human intestine”. Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy.

- Helander, Herbert F.; Fändriks, Lars (2014-06-01). “Surface area of the digestive tract – revisited”. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology.

- Bowen, Richard. “Gastrointestinal Transit: How Long Does It Take?”. Colorado State University.

- Kim, SK (1968). “Small intestine transit time in the normal small bowel study”. American Journal of Roentgenology.