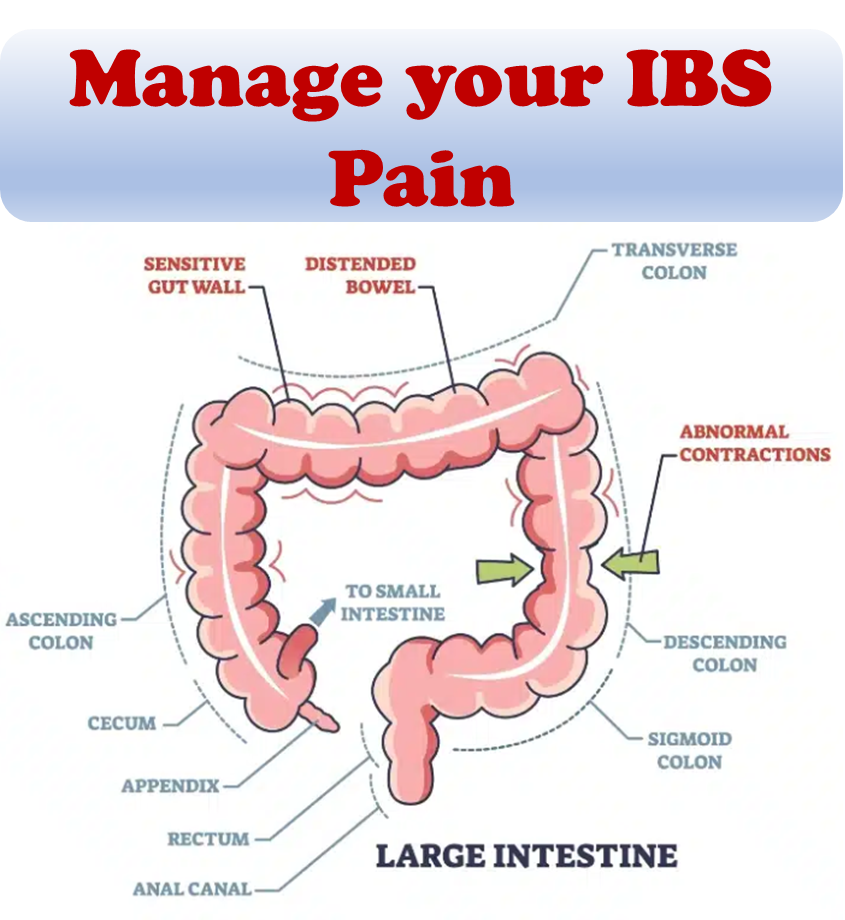

The term IBS cure is subjective and the condition itself is very personal. IBS is typically managed, not cured. The most common way to manage IBS symptoms is to manage one’s diet. It is helpful to keep track of food intake and any associated symptoms or flareups for a timeframe. At the start, it may make the most sense to start with a limited set of food items and slowly expand the list as time goes on. Common food and drinks that can cause discomfort are listed below:

- Gas-producing vegetables

- High fat foods

- Carbonated beverages

- Artificial sweeteners

- Caffeine

- Alcohol

People with lactose intolerance and fructose malabsorption need to pay additional care to rule out causative foods. Elimination diets to remove dairy or high FODMAPs (fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides, and polyols) are other options to explore. Each person’s journey tends to be unique with IBS and a combination of remedies may work best as an “IBS cure”. Check out our overview on IBS.

The personal journey towards an IBS cure

When seeking relief from the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), keeping track of your food intake and associated symptoms is crucial. For a period of 4-6 weeks, it is recommended to start with a limited selection of foods and gradually expand the list over time. For instance, in the first week, you could include steamed vegetables, rice, and a fruit.

To manage IBS effectively, it is important to be aware of common food and drinks that can cause discomfort. These include gas-producing vegetables, high-fat foods, carbonated beverages, artificial sweeteners, caffeine, and alcohol. Individuals with lactose intolerance and fructose malabsorption should pay extra attention to identifying the foods that trigger their symptoms. Exploring elimination diets to remove dairy or high FODMAPs (fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides, and polyols) is also an option worth considering. It is essential to acknowledge that each person’s journey with IBS is unique, and a combination of remedies may provide the best “IBS cure.” For more information on IBS, refer to our comprehensive overview.

IBS tests and diagnosis

The diagnosis of IBS is typically based on a comprehensive medical history, physical examination, and tests aimed at ruling out other conditions like celiac disease and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Once other conditions are ruled out, your healthcare provider may use the Rome criteria – these criteria involve assessing abdominal pain or discomfort occurring at least once a week in the past three months, along with at least two of the following: pain related to bowel movements, changes in bowel movement frequency, or changes in stool consistency. The IBS may then be categorized into four types for treatment purposes based on predominant symptoms: constipation-predominant, diarrhea-predominant, mixed, or unclassified.

Your provider will also evaluate if you have any additional symptoms that could suggest a more serious condition, such as:

- Onset of symptoms after the age of 50

- Unexplained weight loss

- Rectal bleeding

- Fever

- Nausea or recurrent vomiting

- Abdominal pain unrelated to bowel movements or occurring at night

- Persistent diarrhea or diarrhea interrupting sleep

- Anemia related to low iron levels

If you experience these symptoms or if initial IBS treatment proves ineffective, additional tests may be necessary. These tests may include:

- Stool studies to check for infections or malabsorption issues

- Colonoscopy, which uses a flexible tube to examine the colon

- CT scan to obtain images of the abdomen and pelvis

- Upper endoscopy, where a tube is inserted into the esophagus to visualize the upper digestive tract and collect samples for biopsy or bacterial analysis, particularly if celiac disease is suspected

Laboratory tests may involve:

- Lactose intolerance tests to assess the ability to digest dairy products

- Breath tests to detect bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine

- Stool tests to examine for bacteria, parasites, or bile acid presence

These diagnostic procedures and tests help in determining the presence of IBS and ruling out other potential causes of your symptoms.

Treatment options

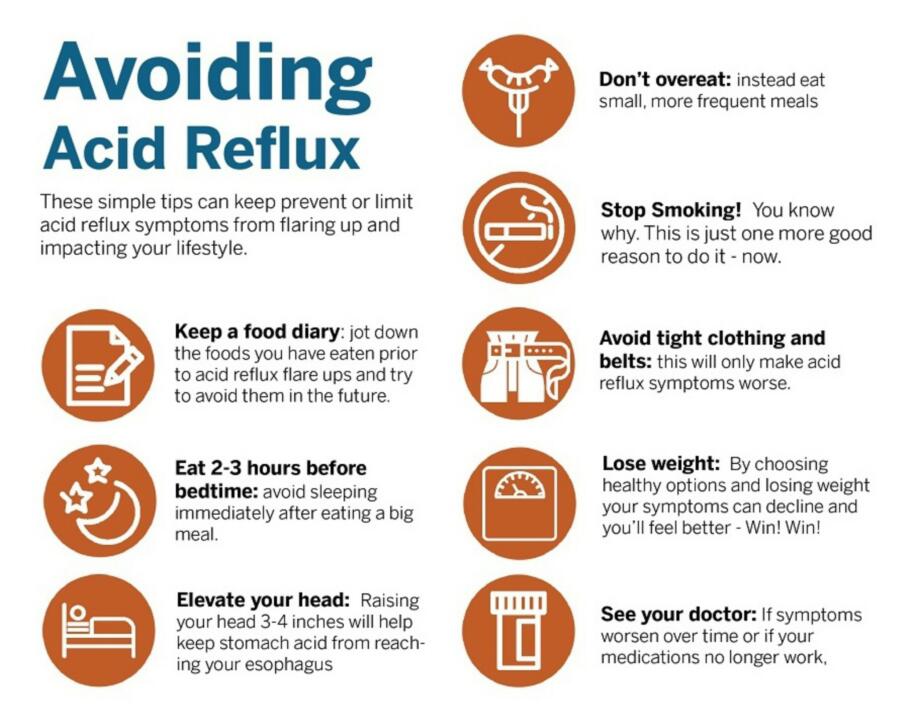

Managing and alleviating symptoms is the primary focus in treating IBS, aiming for a better quality of life. Depending on the severity of your symptoms, treatment options may vary. For mild symptoms, implementing changes in your diet and lifestyle, as well as stress management, can often be effective. Consider the following:

- Identify and avoid trigger foods that worsen your symptoms.

- Incorporate high-fiber foods into your diet.

- Stay adequately hydrated by drinking plenty of fluids.

- Engage in regular exercise.

- Ensure you get sufficient sleep.

To assist with dietary adjustments, consulting a registered dietitian can provide valuable guidance. If your symptoms are moderate or severe, counseling may be recommended, particularly if you have depression or stress exacerbates your symptoms. Based on your specific symptoms, medications may be prescribed, including:

- Fiber supplements: Psyllium (Metamucil) with ample fluids can help manage constipation.

- Laxatives: Over-the-counter options like magnesium hydroxide oral (Phillips’ Milk of Magnesia) or polyethylene glycol (Miralax) can be used if fiber alone doesn’t relieve constipation.

- SSRI antidepressants: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) like fluoxetine (Prozac) or paroxetine (Paxil) can be beneficial if you experience pain, constipation, and depression.

- Pain medications: Severe pain or bloating can be relieved with medications such as pregabalin (Lyrica) or gabapentin (Neurontin).

- Anti-diarrheal medications: Over-the-counter medications such as loperamide (Imodium A-D) can be beneficial for controlling diarrhea. Bile acid binders like cholestyramine (Prevalite), colestipol (Colestid), or colesevelam (Welchol) may also be prescribed but can potentially cause bloating.

- Anticholinergic medications: Medications like dicyclomine (Bentyl) can help alleviate painful bowel spasms and may be prescribed if you experience bouts of diarrhea. Side effects may include constipation, dry mouth, and blurred vision.

- Tricyclic antidepressants: In lower doses, antidepressants such as imipramine (Tofranil), desipramine (Norpramin), or nortriptyline (Pamelor) can reduce pain by inhibiting intestinal nerve activity. These may be suggested if you have diarrhea and abdominal pain without depression. Common side effects, which may be minimized by taking the medication at bedtime, include drowsiness, blurred vision, dizziness, and dry mouth.

Medications specifically approved for certain cases of IBS include:

- Rifaximin (Xifaxan): This antibiotic can be used to reduce bacterial overgrowth and associated diarrhea.

- Lubiprostone (Amitiza): Prescribed for women with IBS and constipation, lubiprostone increases fluid secretion in the small intestine, facilitating stool passage.

- Linaclotide (Linzess): Similar to lubiprostone, linaclotide enhances fluid secretion in the small intestine, aiding in bowel movements. Diarrhea can be a side effect, but taking the medication before meals may help.

- Alosetron (Lotronex): This medication relaxes the colon and slows down the movement of waste. It is prescribed only by providers enrolled in a special program and is intended for severe cases of diarrhea-predominant IBS in women unresponsive to other treatments.

- Eluxadoline (Viberzi): By reducing muscle contractions and fluid secretion in the intestine, eluxadoline can alleviate diarrhea. It is also known to improve muscle tone in the rectum.

Potential future treatments being investigated for IBS include fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). FMT involves introducing processed stool from a healthy individual into the colon of an IBS patient to restore a healthy gut microbiome. Clinical trials are currently underway to explore this option further.

Exploring the role of fiber

Dietary fiber has long been recognized as beneficial for various gastrointestinal conditions, including IBS. A deficiency in dietary fiber intake is considered a primary cause of IBS. Increasing the amount of dietary fiber consumed is a common recommendation for IBS patients.

Dietary fiber can be divided into two types: soluble and insoluble. Soluble fiber dissolves in water and can be further categorized as short-chain or long-chain carbohydrates, fermentable or non-fermentable. Short-chain, soluble, and highly fermentable fiber, such as oligosaccharides, can lead to excessive gas production, resulting in symptoms like abdominal pain, bloating, and flatulence. In contrast, long-chain, soluble, and moderately fermentable fiber, like psyllium, produces less gas and does not cause excessive symptoms.

Physicians often advise IBS patients to increase their daily dietary fiber intake to 20-35 grams to regulate bowel movements and reduce abdominal pain. Supplementation with long-chain, soluble, and moderately fermentable fiber, such as psyllium, has shown improvements in overall IBS symptoms. Additionally, consuming smaller, more frequent meals instead of the traditional three main meals can alleviate stress on the digestive system.

FODMAPs, which are short-chain carbohydrates poorly absorbed in the small intestine, have been shown to significantly improve symptoms when restricted in the diet. A low-FODMAP diet, which globally trims these carbohydrates, can be helpful for individuals with IBS, particularly when other dietary and lifestyle measures have been unsuccessful. However, it is crucial to ensure a proper diagnosis of IBS before pursuing this diet, as it may lead to the misdiagnosis of other conditions like celiac disease.

Physical activity has also demonstrated potential benefits for IBS. Regular exercise has been shown to improve IBS symptoms, including severity and constipation. Therefore, it is recommended that all IBS patients engage in regular physical activity, as advised by the British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines.

Various medications can be considered for symptom management. Antispasmodics, such as dicyclomine, can provide relief for cramps and diarrhea. Laxatives, like polyethylene glycol, sorbitol, and lactulose, can be helpful for those who do not.

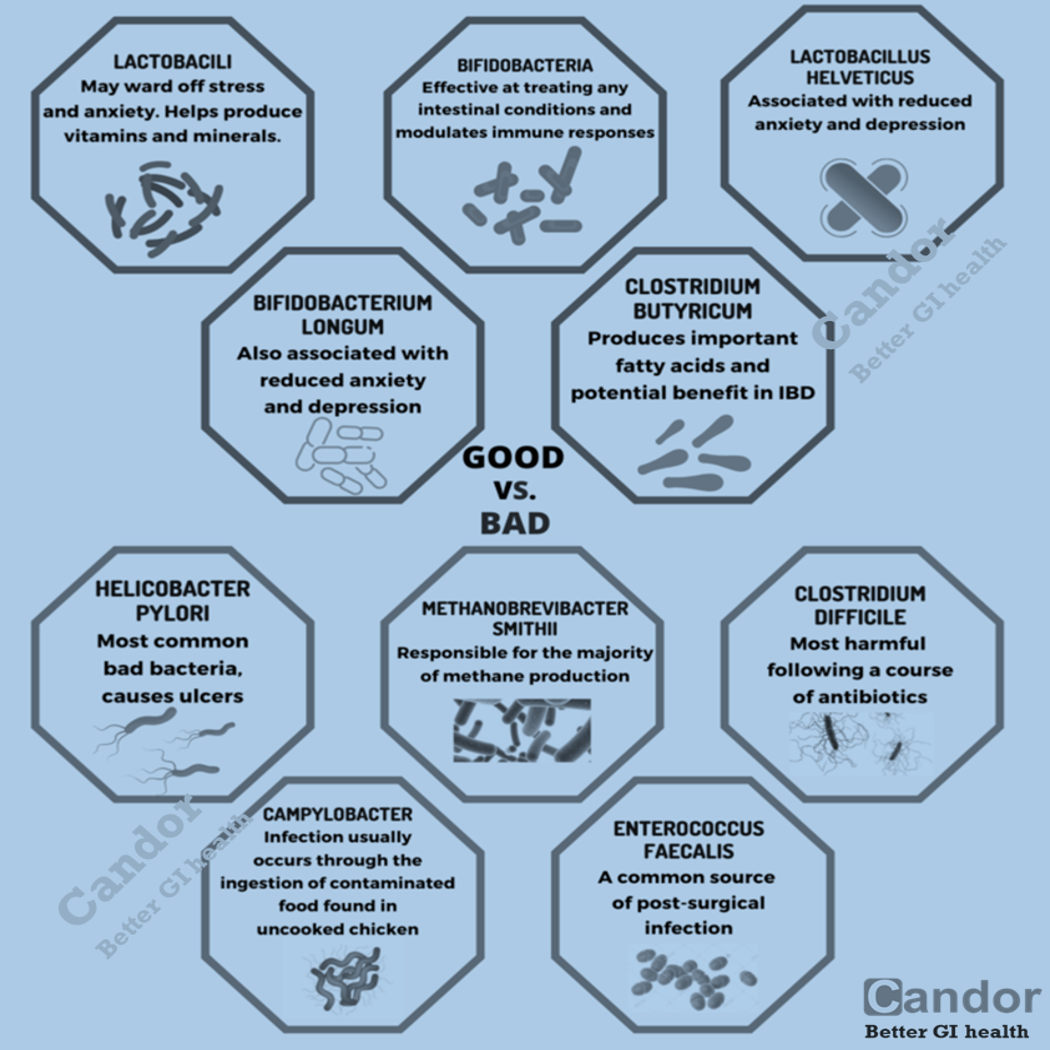

Probiotics

In addition, your healthcare provider might suggest incorporating probiotics into your treatment plan. Probiotics are live microorganisms, primarily bacteria, that resemble the beneficial microorganisms naturally present in your digestive system. While the use of probiotics for treating IBS is still being researched, they may offer potential benefits.

To ensure safety, it’s important to consult with your doctor before starting probiotics or any other complementary or alternative medical approaches. If your doctor recommends probiotics, have a discussion about the appropriate dosage and duration of use.

Mental health therapies

In addition to medical treatments, your healthcare provider may suggest mental health therapies as part of your IBS management. These therapies aim to improve your IBS symptoms by addressing the psychological factors associated with the condition. Some of the commonly used mental health therapies for IBS include:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): CBT focuses on identifying and modifying negative thought patterns and behaviors that contribute to IBS symptoms. It helps you develop coping strategies and promotes positive changes in your mindset.

- Gut-Directed Hypnotherapy: This therapy involves the use of hypnosis, a state of deep relaxation and heightened focus, to alleviate IBS symptoms. A trained therapist guides you through hypnosis sessions aimed at calming the gut and reducing symptoms.

- Relaxation Training: This therapy teaches techniques to relax your muscles and reduce stress, which can help manage IBS symptoms. Techniques such as deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and mindfulness meditation may be incorporated.

These mental health therapies can complement medical treatments and provide a holistic approach to managing IBS. Discuss with your healthcare provider to determine which therapy may be most suitable for your specific needs.

References:

- Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Schiller LR, Schoenfeld PS, Spiegel BM, Talley NJ, Quigley EM (January 2009). “An evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome” (PDF). The American Journal of Gastroenterology.

- Dionne J, Ford AC, Yuan Y, Chey WD, Lacy BE, Saito YA, Quigley EM, Moayyedi P (September 2018). “A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Evaluating the Efficacy of a Gluten-Free Diet and a Low FODMAPs Diet in Treating Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome”. The American Journal of Gastroenterology.

- Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, Soffer EE, Spiegel BM, Moayyedi P (September 2014). “Effect of antidepressants and psychological therapies, including hypnotherapy, in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis”. The American Journal of Gastroenterology.

- Gibson PR, Shepherd SJ (February 2010). “Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: The FODMAP approach”. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology.